Written by Dr. Shelagh Roxburgh and Dr. Candice Shaw

The story of trafficking in Indigenous peoples is long and complex. It is also well hidden in Canada, where the reality of settler colonialism is obscured so that dominant myths about Indigenous peoples can be perpetuated, and settler privileges can be protected. Breaking through the dominant, colonial narratives about violence in our society is a challenge – but progress is being made. Increasingly, anti-trafficking advocates and allies are contesting dominant frameworks that erase Indigenous peoples, include them as minorities, or portray the exploitation of Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse through the lens of criminalization.1

Dominant anti-trafficking narratives have worked to increase awareness of trafficking through simple messages that rely on a strong dichotomy between victims and perpetrators.2 In these stories, young girls are preyed upon by men who kidnap them, hold them hostage, and exploit them for money. These representations of human trafficking inform people’s understanding of who is a victim and who is a criminal and allows them to apply these categories in the identification of trafficking.3 Unfortunately, these stories overlook important historical and contemporary complexities, such as colonialism, racism, and the role of the state as a ‘complicit criminal.’4

Anti-trafficking initiatives have long held the state as a source of protection and as a provider of rights, rescuing victims from violence and punishing offenders through criminal and legal processes. Rarely is the state considered as a potential source of violence or, more specifically, as a colonial system that creates benefits for the settler population explicitly at the expense of Indigenous peoples. Yet, colonialism is at the core of human trafficking in Canada. Colonialism underlies the inability of the Canadian justice system to recognize Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse peoples as victims and “prevents them from receiving the assistance and care that would accompany that recognition.”5 Coming to terms with the full scope of human trafficking also means acknowledging the long history of this crime as well as the broader social context of exploitation in Canada, where the victimization of Indigenous women, girls, and gender diverse peoples is normalized and endemic.6

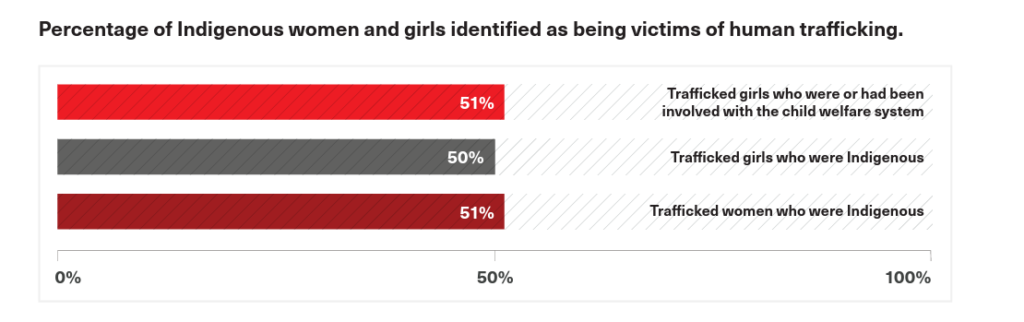

Hints of this reality are visible in evidence provided by civil society efforts to reveal the true scale of trafficking in Canada. As mentioned above, in 2014 the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada released their report, “NO MORE” Ending Sex-Trafficking in Canada. The Task Force conducted a survey of 534 agencies across Canada and heard from 46 service providers who attended a roundtable on trafficking. The Task Force found that when asked “details about the trafficked and sexually exploited women and girls they served, the organizations estimated:

- 51% of trafficked girls were or had been involved with the child welfare system.

- 50% of trafficked girls and 51% of trafficked women were Indigenous.”7

It is important to note that these two categories are not mutually exclusive; Indigenous children are grossly overrepresented in child welfare systems, comprising more than half of children in care across the country.8

Though it is estimated that Indigenous women and girls are disproportionately affected, this over-representation is not reflected in national conversations about human trafficking or in many anti-trafficking initiatives. In a study of antitrafficking efforts in Canada, Dr. Julie Kaye from the University of Saskatchewan traces the invisibility of Indigenous experiences today to early anti-trafficking discourse that emerged “alongside concerns over white slavery.”9 This twentieth century discourse focused heavily on the narrative of innocent girls who were coerced and exploited, drawing on the colonial imagination of ‘innocence’ as “largely synonymous with whiteness and purity.”10 This construction of the ideal victim draws on and reinforces the “enduring colonial racist and sexist stereotype of dirty, promiscuous, and deviant Indigenous femininity,” and facilitates the erasure of Indigenous victims, normalizing and naturalizing their experiences of violence.11

The erasure of Indigenous experiences is extended to anti-trafficking responses that rely on colonial state structures; victims are provided support and protection through the same violent systems that oppress Indigenous peoples.12 The disconnect between dominant anti-trafficking responses and the colonial context in Canada is exemplified in anti-trafficking laws and definitions that echo colonial processes The erasure of Indigenous experiences is extended to antitrafficking responses that rely on colonial state structures; victims are provided support and protection through the same violent systems that oppress Indigenous peoples. of dispossession, forced relocation, the abduction of children, and coercive exploitation.13 The consequences are numerous. Of particular importance: Indigenous victims are alienated by anti-trafficking discourses that not only fail to acknowledge their experiences, but which also reinforce the processes by which they are victimized.

This in turn means that Indigenous victims may be less likely to seek support because their experiences will not be understood, or they will be directed to the colonial state by anti-trafficking responses. Because their experiences of trafficking are further normalized by anti-trafficking discourses, Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse peoples may also be less able to identify their own experiences as trafficking. In Canada, these biases have created a two-tier advocacy environment, where large anti-trafficking advocates operate separately from Indigenous community-based organizations, in part, because many antitrafficking advocates are unable to confront colonial violence within “mainstream Canadian systems.”14

It is difficult for many to confront and accept that Indigenous peoples are presently, and have been colonized and oppressed, and are subjected to casual violence across Canada. Indigenous peoples are often made to feel that their lives are not valued, in fact, there is an implicit systemic expectation that they will be victimized and are not worth helping.15 For Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse people, it is common that service providers expect exploitation to occur, creating a climate of “professional indifference” where Indigenous girls are “treated differently by police and service providers.”16 It is also common that Indigenous victims are blamed for the violence they are subjected to or are criminalized as opposed to being helped. These responses reflect deep colonial biases, and a willingness to ignore colonial violence and assume that Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse peoples can protect themselves from an unsafe environment.17

The trafficking of Indigenous women, girls, and gender-diverse peoples has been normalized in Canada through historical processes that have been transformed over time, but which persist as ubiquitous expressions of colonial violence. Before Canada existed, the trafficking of Indigenous women and girls began with the introduction of slavery by French and British colonists, who bought and sold Indigenous slaves until the practice was abolished in 1834.18 Shortly after the abolition of slavery, the ‘reserve,’ or reservation system was introduced, in which entire nations were forcibly relocated onto to parcels of land that they could not leave without permission from Indian agents. In this system, Indigenous peoples were separated from their lands and livelihoods, and in many cases, the extermination of their hunting rights and food sources, such as the eradication of the buffalo, served the intended purpose of coercing Indigenous peoples to comply with government demands.

Indigenous peoples were forced into poverty and dependence by the colonial state, and then their lands and people were exploited under duress, their children were abducted and committed into Residential Schools. Meanwhile, Indigenous women and girls were victimized by Indian agents, the North-West Mounted Police, and settlers in exchange for access to essential goods.19 The forced relocation of entire Indigenous communities continued well into the late 1960s, and the abduction of Indigenous children continued in the form of the Sixties Scoop, and arguably persists in today’s Millennial Scoop.20 For Inuit communities, intensive colonization, forced relocations, the slaughter of sled dogs to prevent movement and to limit livelihoods, and the exploitation of women and girls have occurred within one lifetime, fundamentally altering Inuit lives and devastating communities.21

Throughout these complex episodes, violence, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking have dominated colonial policies to eradicate and suppress Indigenous peoples and have been forcibly integrated into Indigenous peoples lived realities and daily survival. Adding to this complexity is the ongoing pressure of poverty which exposes Indigenous women and girls to predators and facilitates their criminalization.22 Rather than offering protection, the criminal justice system often targets Indigenous women and girls through the biased application of the law and through violence perpetrated by police officers.23 Contrary to the dominant anti-trafficking response that relies on state protection and the support of social services, the National Task Force on Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls in Canada found that 71% of trafficking survivors “reported being forced to have sex with doctors, 60% with judges, 80% with police, and 40% with social workers.”24

It is understandable that Indigenous women and girls who are being exploited and trafficked may have difficulty identifying their experiences as trafficking, may be reluctant to reach out to police and mainstream social services, or may be unwilling to identify themselves as Indigenous when seeking help. Because of these factors, Indigenous women and girls are less likely to be captured by police data, social service organizations, and dominant anti-trafficking initiatives.

These complexities also highlight the need to expand trafficking discourse to include challenging conversations that fall outside the typical storyline. Some trafficking stories do involve criminal predators who appear suddenly in someone’s life; others involve trafficking by family or friends for intermittent periods of time.

It is also imperative to broach the subject of state and society complicity. Police violence must be addressed. While politicians and news media may celebrate stories of economic development, such as mining or oil, Indigenous communities have long known that these same projects increase exploitation and trafficking.25 Correlations between development projects and violence against Indigenous people, particularly women, girls, and gender-diverse-peoples, are a well-documented phenomenon.

Anti-trafficking narratives must begin to grapple with the complex issue of colonialism and the systemic grooming and mass victimization of Indigenous peoples. It is essential that the boundaries that separate the two spheres of antitrafficking discourse and Indigenous experience are broken down.

The Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking has begun this important work and is opening dialogue with Indigenous organizations across Canada. The inclusion of this research in the Centre’s report, Human Trafficking Trends in Canada (2019-2020), is a testament to this work, and their ongoing work with Indigenous advocates and organizations point to a willingness to bring colonialism into focus and to expand anti-trafficking discourse to include Indigenous experiences. Working together, Indigenous and anti-trafficking advocates can challenge the normalization of violence against Indigenous peoples and begin to address and unsettle the very foundations of violence in our society.

Endnotes

- Sethi, A. (2007). Domestic Sex Trafficking of Aboriginal Girls in Canada: Issues and Implications. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3 (3), 57–71. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7202/1069397ar

- Kaye, J. (2017) Responding to Human Trafficking: Dispossession, Colonial Violence, and Resistance among Indigenous and Racialized Women, University of Toronto Press.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Sikka, A. (2010). Trafficking of Aboriginal Women and Girls in Canada. Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi), 57. Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/57

- Ibid.

- Canadian Women’s Foundation (2014).

- Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2018). Interrupted childhoods: Over-representation of Indigenous and Black children in Ontario child welfare. Ontario Human Rights Commission, Toronto: Canada.

- Kaye 2017.

- Kaye 2017.

- Kaye 2017; Bourgeois, R. (2015). Colonial exploitation: The Canadian state and the trafficking of Indigenous women and girls in Canada. UCLA Law Review. Retrieved from https://www.uclalawreview.org/colonial-exploitationcanadian-state-trafficking-indigenous-women-girls-canada/

- Kaye 2017.

- Kaye 2017

- Bourgeois 2015

- Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2019). Journey to Safe Spaces: Indigenous Anti-Human Trafficking Engagement Report 2017-2018. Ontario Native Women’s Association. Retrieved from https://b4e22b9b-d82644fb-9a3f-afec0456de56.filesusr.com/ugd/33ed0c_1a2b7218396c4c71b2d4537052ca47cd.pdf; Turpel-Lafond, M. E.. (2016). Too Many Victims: Sexualized Violence in the Lives of Children and Youth in Care, Office of the Representative for Children and Youth, Victoria: Canada. Retrieved from https://cwrp.ca/publications/too-manyvictims-sexualized-violence-lives-children-and-youth-care-aggregate-review

- Turpel-Lafond 2016: 32

- Turpel-Lafond 2016: 38

- Sikka 2010.

- Bourgeois (2015); Barman, J. (1997). Taming Aboriginal Sexuality: Gender, Power, and Race in British Columbia, 1850-1900, BC Studies 115/116 (Autumn/Winter)

- Bourgeois 2015

- Wilson, J. (2018). Public Testimony, National Inquiry into Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls TruthGathering Process – Parts II & III Institutional & Expert/Knowledge-Keeper Hearings “Sexual Exploitation, Human Trafficking & Sexual Assault.” Sheraton Hotel, Salon B, St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador, Tuesday October 16, 2018, National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Retrieved from https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/20181016_MMIWG_St-Johns_Exploitation_Parts_2__3_Vol_16.pdf

- Razack, S. H. (2016). Gendering Disposability. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, 28 (2), 285-307. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3138/cjwl.28.2.285

- Palmater, P. (2016). Shining light on the dark places: Addressing police racism and sexualized violence against Indigenous women and girls in the National Inquiry. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, 28(2), 253-284. Retrieved from https://femlaw.queensu.ca/sites/webpublish.queensu.ca.flswww/files/files/PalmaterCJWL2016.pdf

- Canadian Women’s Foundation (2014).

- Ontario Native Women’s Association 2019; Barman 1997.